Back in 1619, a group of enslaved Africans ended up in what was then the British colony of Virginia. Torn from their homeland, they had to leave almost everything behind, but one thing they carried across the Atlantic was their knack for making music, especially the rhythms.

Many of these folks came from places where they spoke tonal languages, meaning the way you say a word often mattered as much as the word itself. In their world, rhythm was king, and melody took a back seat. This strong sense of rhythm helped them build a shared musical identity, giving them a way to communicate through songs and chants about their difficult lives. Music was everywhere in their daily lives, an essential part, not just an add-on.

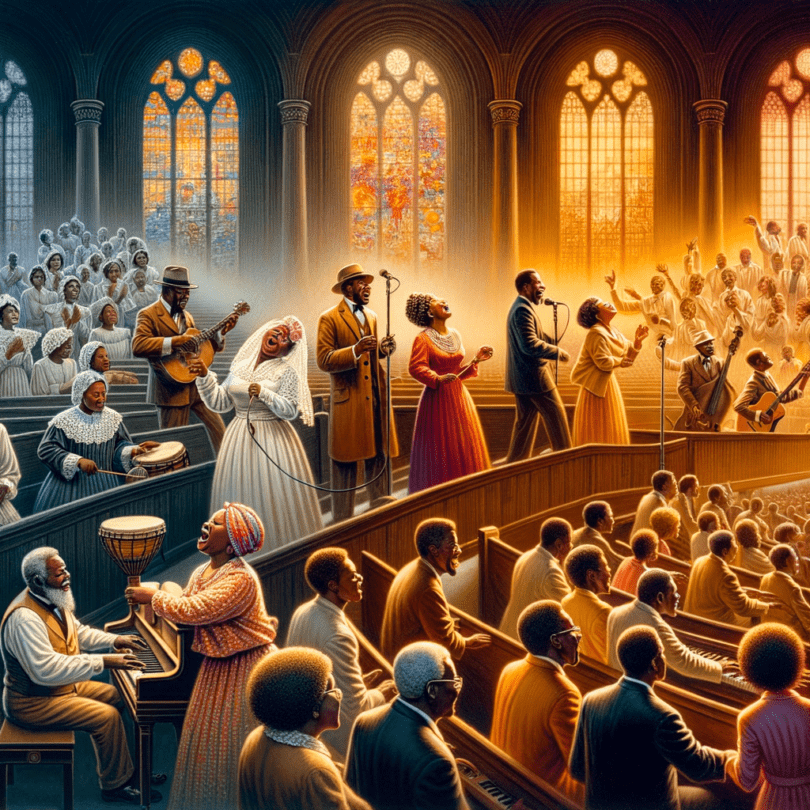

Over time, these rhythms worked their way into work songs, those field shouts, and street calls, often paired with dancing. The roots came from African traditions that loved community involvement and the call-and-response style. One person would lead with a musical call, and the rest would reply with an answer.

I’ve found in my research that when these African rhythms mixed with Western music, they laid the groundwork for African-American genres, especially spirituals and eventually gospel music.

John Gibb St. Clair Drake, a well-known Black anthropologist, noted how Christianity clashed with many African beliefs during slavery times. For many Africans, ideas like sin, guilt, and the afterlife were completely new. In Africa, sin was more of an annoyance you could wash away with something like an animal sacrifice, but in Christianity, especially in the Northern U.S., sin carried deeper, equal-for-all implications.

In 1787, responding to racial discrimination at St. George Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, along with others, left and started the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This church became a haven for the African spiritual songs that had been crafted by enslaved people over centuries. Richard Allen even published a hymnal in 1801 that mixed African musical approaches with Christian hymns.

When slavery ended in 1863, African-Americans moved around the U.S. and took their cultural and religious practices with them, adapting as they went. Later on, people like George White, a professor at Fisk University, started to document and share these spirituals with wider audiences. The Fisk Jubilee Singers really brought this music into mainstream America with their tour in 1871, helping to preserve this piece of culture.

The shift from spirituals to gospel music continued as African-Americans moved north during the Great Migration in the early 20th century. In the 1930s, gospel music was evolving with these shifts in religious thought and cultural expression.

Thomas A. Dorsey, often called the father of gospel, played a big role in this transformation. After a personal tragedy, he turned away from his blues roots and started focusing on gospel music, founding the first gospel chorus in Chicago.

Around this time, the Hammond organ began appearing in Black churches up north and spreading to places like St. Louis and Detroit. The organ was versatile, cheaper than a pipe organ, and allowed musicians to blend melodies, harmonies, and rhythms seamlessly. It became central to church services, supporting sermons and music in a style that’s still popular today.

Gospel music’s story keeps unfolding, inspiring countless musicians who continue the legacy and message through their work.